If you read the previous blog, you know that Charles Darwin visited the Galapagos Island in 1835. During his five weeks there, the variety of mockingbirds, finches, endemic birds, reptiles, and plants captured his attention. These species all contributed to his development of the Theory of Evolution.

While there, he collected specimens of the small birds that he thought were blackbirds, gross-bills, and finches found on various islands. He returned to England in October 1836 with thirty-one specimens of what would become the Darwin Finches.

Within a month of returning to England, he donated some of his specimens to the Geological Society of London. Ornithologist John Gould studied those birds and reported a “series of ground finches which are so peculiar” [formed] “an entirely new group, containing 12 species.” It was Gould who first realized the connection to a single founding species.

Currently, there are 17 species of Galapagos Finches on various islands. During our ten-day visit, we found eleven of those species and I secured images of nine.

The images below represent the species I photographed. For some, the images include both male and female bird. Review the images below and see if you can notice the differences and maybe appreciate Darwin’s challenge.

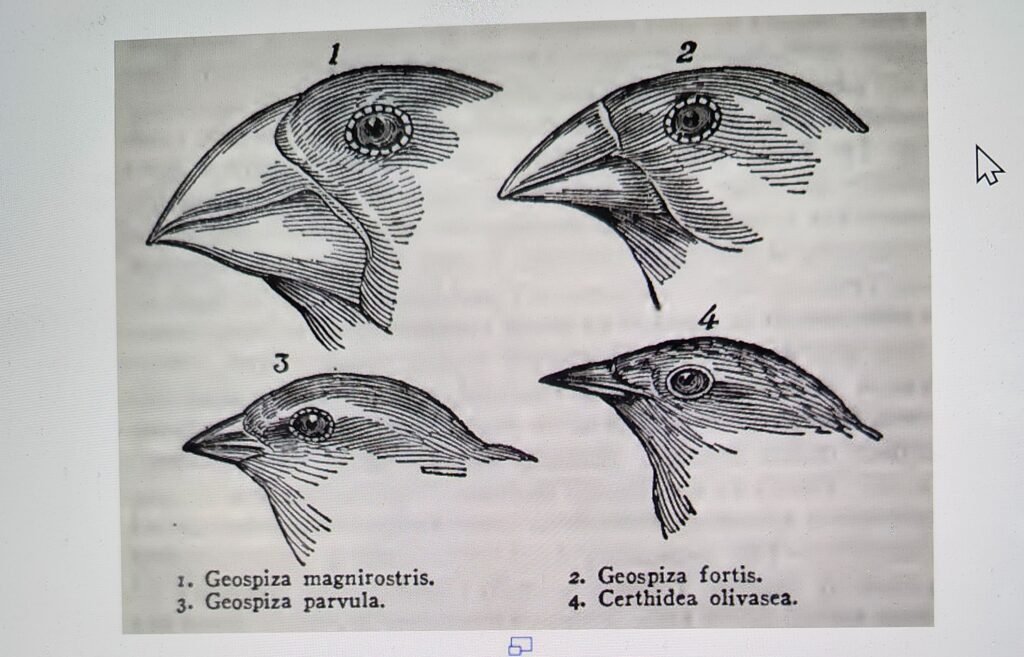

It was in his first book, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H. M. S. Beagle Round the World. Second Edition 1845, (later shortened to The Voyage of the Beagle) that he wrote about the birds of the Galapagos Islands. The book included this image and this description.

“Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.” https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/944/pg944-images.html#link2HCH0017

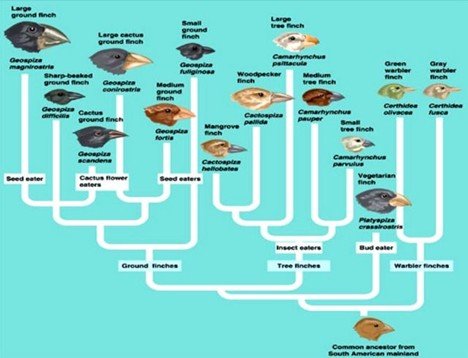

In his chapter on the Galapagos Islands, Darwin says, “The remaining land-birds form a most singular group of finches, related to each other in the structure of their beaks, short tails, form of body and plumage: there are thirteen species, which Mr. Gould has divided into four sub-groups.” The chart below shows the sub-groups, now full genera and how the birds evolved into their respective species. The original chart image can be found at this link. cd72e8731d8c62f1ff7d184019a0f256.jpg (640×489)

Studies conclude that all these birds evolved from a single species of bird that found its way to the Galapagos Island from South America. They are broken up into the genus Certhidea which includes the two species of Warbler-Finch, the Vegetarian Finch (the only bird in the genus Playspiza), five species in the genus Camarhrynchus, the Mangrove Finch, Woodpecker Finch, Small Tree-Finch, Medium Tree-Finch, and Large Tree-Finches, and finally the nine Geospiza species, the Ground-Finches and Cactus Finch.

Below, I will show the photographs I captured and attempt to explain how it is different. Can you match my images with the species in this chart?

Because we did not visit the islands they live on, we did not see the Sharp-billed Ground-Finch, Mangrove Finch, nor the Vampire Ground-Finch (yes it eats Nazca Booby blood it draws by pecking at the base of the tail feathers of the nesting birds). Also, I missed my opportunity to get a picture of Vegetarian Finch (it eats mostly leaves) and most of the Tree-Finches.

I’ll start with the two Warbler-Finches of the genus Certhidea.

The Green Warbler Finch, the smallest of all of the Darwin Finches, has a delicate bill better designed for picking up small animals like insects and spiders. They are found on a number of islands preferring moist forests.

The Grey Warbler Finch is also a tiny bird with a thin, sharp beak. Until recently (around 2008), it was considered to be the same species as the Green Warbler Finch. While it occurs on many of the same islands as the Green Warbler-Finch, it prefers drier habitats. More common than the Green Warbler-Finch, this species can be further split into eight subspecies. Most subspecies can be found on only one island.

Of the five Tree-Finches in the genus Camarhynchus, the only one I was able to capture an image of was the Woodpecker Finch. The others are the Small, Medium, and Large Tree-Finch, plus the Mangrove Finch.

The Woodpecker Finch feeds along the branches and trunks of trees much like a woodpecker. Without a chisel-like bill, it works the rotten wood and surface of the trees. Occasionally, it will craft a tool by forming a small branch into a perfectly shaped and length spear to extract the insects.

Also found on numerous islands, this species is further divided into three subspecies.

The real fun begins when one attempts to separate the nine species of Ground-Finches. Frequently found feeding on the ground, they are primarily seed eaters. To this end, they have big strong cardinal or sparrow type bills.

All the images below are Small Gound Finches. These common birds appear on most islands and adapt to a wide array of habitats and conditions much like a House Sparrow. As a small bird with a “small” bill, they feed on the smaller seeds which can be abundant during the El Niño years (high rainfall). They suffer in the La Niña years of low rainfall as the seeds of the plants that survived were larger and harder.

The widespread Medium Ground Finch looks much like the Small Ground-Finch but are larger with a heavier bill. This adaptable bird can be found on many of the islands. Peter and Rosemary Grant studied these birds extensively. Jonathan Weiner ‘s Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Beak of the Finch details how the Grants discovered that with the vacillating El Niño and La Niña weather events, this species’ beak grew or shrank so it could consume the available seeds.

By now, you have intuited that whoever bestowed the common name to the Darwin Finches was not very creative. Large Ground-Finch lives up to its name. This large-billed bird can eat the seeds with the strongest covers. It prefers drier habitats where the plants produce hard coated seeds.

On the island of Genovesa, the Ground-Finch differs enough from all the others to warrant being a separate species, the Genovesa Gound-Finch. This is the only Ground-Finch found on this island, which is far from the other main islands. The bird is small, like the Small-Ground Finch. These images are of females, the male is mostly black. Compared to the Small-Ground-Finch, note the longer, thinner bill.

The Island of Española also has its own Ground-Finch, the Española Gound-Finch. Formerly known as the Española Cactus Finch, this large (compare to the Small Ground-Finch in the first image) heavily billed bird can only be found on Española Island. They feed primarily on the Prickly Pear cactus (Opuntia sp.) eating every part but the roots.

The two Cactus-Finches, species so closely related to the Ground-Finches scientists thought the Española Ground-Finch was a Cactus-Finch. There are two species.

The first and most common has the insightful common name of Common Cactus-Finch.

This medium sized bird differs from the other Ground-Finches (all of which are in the genus Geospiza) by having a longer, “thinner” bill and by its preference for the seeds from Opuntia cactus.

As recently as 2015, the Genovesa Cactus-Finch was considered a subspecies of the Large Cactus Finch, which was split into this species and the Espanola Ground-Finch. It turns out the Genovesa Cactus-finch is more closely related to the Common Cactus-Finch than it is to its doppelganger the Española Ground-Finch. Its huge bill allows it to feed on the cactus plants.

Not only was it the variety of similar species Charles Darwin found on the Galapagos Islands that helped him formulate his theory of evolution, but it was also how the many islands hosted similar looking but different species of finches and mockingbirds. During his travels, he would notice how many islands held endemic (found nowhere else) species of land birds, but few endemic sea birds. This helped him visualize how a physical barrier like a sea can separate individuals that then evolve into separate species.

The birds covered in these two blogs provide examples of just a few of the 250 vascular plants, 20 reptiles, five mammals, six seabirds, 22 land birds, two marine mammals, 86 fish, and over 1,200 terrestrial invertebrates which are endemic species.

References

Nelson, Richard William. Fate of Darwin’s Finches https://darwinthenandnow.com/fate-of-darwins-finches/ March 10, 2020.

Cromie, William J. How Darwin’s finches got their beaks. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2006/07/how-darwins-finches-got-their-beaks/ July 24, 2006.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Voyage of the Beagle. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/944/pg944-images.html Noija, Maxime.

John Gould’s Influence in the Development of Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection. https://www.heritage-prints.com/john-goulds-influence-in-the-development-of-charles-darwins-theory-of-evolution-by-natural-selection/

You’ll Only Find These Creatures in the Galápagos – A-Z Animals Slideshows

Photos by Bob Mercer